Teaching a dance class can be a lot like teaching a language class. I’d know. I teach both.

Let’s begin with some basic similarities:

- Dance and language classes are often categorized by skill/proficiency level. Many dance academies offer beginner, intermediate, and advanced tracks for students so that they may receive content appropriate to their level of dancing. Language classes have similar nomenclature. For instance, this semester I’m teaching a Spanish language class titled “Advanced Grammar and Composition.”

- Dancing engages analog skills to language learning. In language learning, there are four skills the learner needs to learn and master to become fully proficient: speaking, listening, reading, and writing. Arguably, we engage in the first three of these skills while dancing. Indeed, whomever is leading “speaks,” and whomever is following “listens”— the roles can reverse, of course; and we “read” the facial expressions of our partner to assess whether they are enjoying the dance. If we are feeling poetic, even the latter skill can be used in this metaphor; for it can be argued that we “write” with our hands and feet as we execute turn patterns. We tell a story.

- Dance classes, like language classes, are not lectures. Language classes are very much the back-and-forth between the teacher and the students, and among students themselves. Sure, there is an explicit instruction component, but good language teachers spend most of their times getting students to practice the language through any combination of the four skills mentioned above. Similarly, dance classes allocate time for students to practice with music and with each other the content of that day’s lesson.

- Ultimately, the goal of both types of classes is to push learners toward autonomy. A language class is all about giving students the necessary tools to engage with the language successfully when teachers are not there. Not every aspect of language can be covered in a classroom, and at some point, while out in the “real world,” language learners will encounter themselves in communicative situations which require them to think about language, not as a static phenomenon, but a dynamic, ever-changing process. Good language teachers foster skills that help learners adapt and respond to these new situations. Likewise, the goal of dance classes is not simply to teach turn patterns—or at least I think that shouldn’t be the goal—but to teach students the necessary skills to eventually go out into the “real world” and dance with people of all levels. And learners can only do that if they see dancing as they see language: not a static combination of turn patterns—or string of words—put together, but as meaning being constantly negotiated in the give-and-take that is a conversation/dance between two people.

Given these similarities between dance and language classes, it seems like a lost opportunity to me to not take advantage of the intersection created by looking at dance and language learning through the same lens. This seems particularly beneficial to me because, unlike the field of language learning, there is little-to-no research on the instruction of what people call Latin dances here in the U.S. Most of what teachers teach in their dance classes follows the format and/or techniques of what they have seen other teachers do, or the teachers from whom they personally learned. At dance congresses, when instructors from different parts of the country meet in one place, there is no such thing as an “instructor workshop” where new class management strategies and/or teaching methodologies are shared. There is no “course” dancers take to become instructors, exams they need to pass, certificates earned. From what I’ve observed, the transition from “dancer” to “dance instructor” is often a simple one: if you are a good dancer, you can teach.

In short, as far as methodology goes, a lot of “Latin dance” instructors are pretty much playing it by ear.

And this is where the similarities between dance and language classes come to a sudden, screeching halt. Unlike teachers of “Latin dances,” most people who want to teach language need to take at least one teaching methodology course before they even stand in front of any student—the implication here being that simply knowing how to speak the language does not mean you are qualified to teach it. Among other things, these classes help prospective teachers get up-to-date with the latest research in the field of language learning; introduce them to the different language processing strategies that research has shown their students use; and, most importantly, these classes delve into teaching strategies and methodologies that can help them become better language teachers and, by extent, foster better language learners.

Should “Latin” dance instructors go through a similar process before they teach? The question falls outside of the scope of this post. But if we can agree that language classes can be very similar to dance classes—and I hope that I made a good-enough case that you do agree with me on this—, then perhaps looking at good methodological practices from the language classroom can be a possible way to start to bridge that gap between the better-prepared language teachers and the less-prepared dance instructors.

That’s where the 80/20 rule of language instruction comes in.

Also known as the Pareto principle, the 80/20 rule states that 80% percent of the effects come from 20% of the causes. In language instruction, this principle has been modified to fit the necessities of the language classroom where, again, the objective is to push learners toward autonomy. The 80/20 rule of language instruction essentially stipulates that 20% of the time in the classroom should be spent on explicit instruction, while the remaining 80% of the time should be allocated toward student practice. Language is learned through practice, and learners cannot practice if the instructor spends most of the class time talking. That’s why this rule works and is accepted throughout many successful language classroom everywhere: it gets students to practice, practice, practice; to talk to each other and negotiate meaning; to become aware of which things they can say and cannot; to reflect when communication breaks down; to find a way to fix it when it does. All of this helps the students prepare for communicating in the real world.

This does not mean that the teacher doesn’t do anything. The role of the teacher is to come up with communicative activities that will maximize language production among students—among other things which I will not go into detail—and supervise the interactions, often offering feedback, help, or corrections as needed. After the usual ten minutes a grammar lesson should last (20% of a typical 50-minute class), the teacher, then, becomes a “communication facilitator.”

(Those perhaps aghast by the idea that language teachers may not be doing much “teaching” in the language classroom should know that studies have shown, time and again, that language learners will learn language regardless of instruction; and that instruction seems to only slightly accelerate the rate of acquisition. And that, again, it is the students who need to practice, not the teacher. These are aspects of instruction that language teachers review in their methodology classes precisely because a lot of prospective teachers come in thinking that teachers should carry all the weight of the classroom on their shoulders—we call this the “Atlas Complex”—and forget that it is the students who, ultimately, have to do the learning.)

The 80/20 rule works great in language classrooms. And seeing as dance classes can be very similar to language ones, students in dance classes may benefit tremendously from instructors applying this rule. Let’s see how.

The typical “Latin” dance class nowadays follows this general format: there is a turn pattern or two that are taught throughout most of the lesson. This involves the teacher(s) breaking down every eight-count of the turn patterns and having students repeat it with them several times; then the instructor(s) move to the next eight counts and there is more repetition; then again; and on and on until the turn pattern is done. Sometimes a song will be played every now and then to give students the chance to practice what they have been taught; sometimes, students practice at the end.

Many dance classes follow this format, which means that, if your class follows this format, most of the class is spent teaching/learning a turn pattern.

Which in turn means that most of the class was dedicated to instruction, not practice. Meaning the instructors talked quite a lot.

Now, it can be argued that learners were mimicking the instructor the entire time, so they were dancing—and then dancing some more when the music played. So, in truth, learners practiced the entire time, even as the instructors received most of the attention.

But practiced to what end, exactly?

There is a very common occurrence in language classrooms, and it begins with the teacher saying, “Repeat after me.” We call it a “drill.” Drills can be helpful with pronunciation, but as a whole, drills can be highly ineffective. For instance, I can make you repeat twenty different phrases in a language you don’t know. Will you learn anything? Of course not. You won’t even know what you are saying.

When a dance class is centered on a turn pattern, the entire lesson becomes a sort-of mechanical drill. It’s all about the “Repeat after me.” What the instructor does, the learner does. And when the music plays, it is played so that what was taught can be practiced.

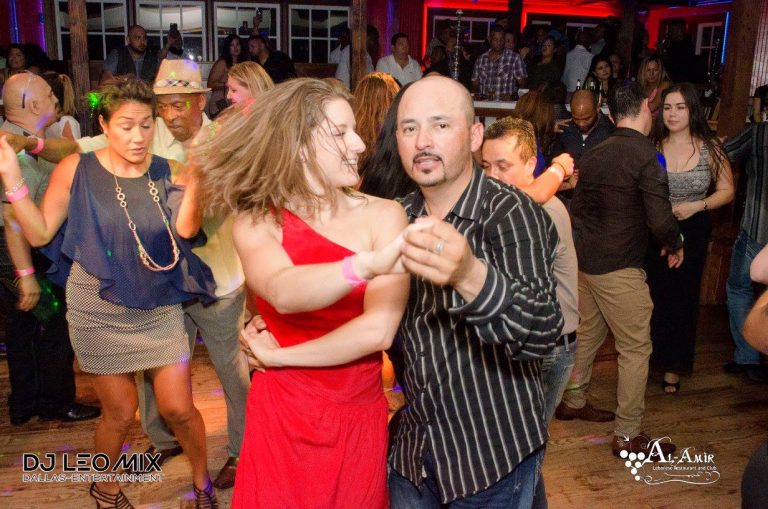

So, yes, there is practice. But if we accept the proposition that the goal of any dance lesson is, like in language, to prepare learners for dancing out in the “real world,” then a lesson centered on a turn pattern like the one I described above, falls short of that goal. A lesson which objective revolves around the execution of a turn pattern is like a language lesson which main objective is to do drills. In classes like these, dance, like language, is seen as a static system of arbitrary rules. Indeed, if you think about it, there is little leading and following (“speaking” and “listening”) occurring. When learners practice the turn pattern at any point during the lesson, they are executing a known sequence; they know what it supposed to happen. Each dancer can basically execute their part without the other. There is no negotiation of meaning, no room for improvisation; no chance to think about how what is being learned fits into what has already been learned, and how to combine the old and the new information into a completely new turn pattern. That’s what drives the learner toward autonomy and helps them transition from the dance class into the social dance floor.

But much like a drill in language classes gives learners the impression that they are learning the language because they can conjugate a list of irregular verbs in past tense when in truth they can’t utter anything beyond that, the drill-like focus on turn patterns can give learners—specially beginner ones—the idea that they’re learning to dance because they can do a turn pattern when in reality they cannot do anything beyond what they’ve been taught.

That’s why many beginners have such a hard time dancing, or why dancing can seem pretty daunting at that stage. Beginners are taught the dance as a series of turn patterns. Given that beginners don’t know many turn patterns (notice how categories such as “beginner” or “intermediate” are very much turn pattern-oriented), they can understandably run out of material very soon and become discouraged from dancing—or bored, if they find themselves repeating the same things. Moreover, because they were not given the tools to negotiate meaning during class—they did not actually practice leading and following—their attempts at communication often break down when they are dancing socially, which can lead to relentless frustration.

Dance instruction shouldn’t focus so much on turn patterns. Turn patterns should be part of the lesson, but the objective shouldn’t be to get learners to do a turn pattern. That does not push them toward autonomy. What pushes them toward autonomy—again, if we can agree that a dance class’s objective should be to create dancers that can dance successfully outside of the class setting—is having less time to mimic the instructors, and more time to practice among themselves the contents of the day’s lesson—with instructors going around and offering feedback, comments, suggestions, etc., of course; otherwise, it’d become a dance social.

The 80/20 rule of language learning can be adapted very well to a dance class to fit this goal. It maximizes meaningful practice time and gives learners the chance to “play” with the dance; to become aware of things they don’t yet understand, and to cement those things they do; to see what works, and what doesn’t; to attempt to connect the contents of the day’s lesson with that of other lessons.

None of these things could be accomplished if the goal that is set for the lesson is to learn a turn pattern. Instructors need to let go of practices that highlight their role during the lesson and make them center stage, and embrace practices that focus more on getting learners to practice on their own. And that means toning down the emphasis on the turn patterns because what that does is teach learners to mimic what instructors can do, instead of allowing learners to figure out what they can personally do.

With this, I am not saying that turn patterns should not be taught. What I am saying is that turn patterns should play a secondary role in instruction. More beneficial for students—specially beginner ones—would be the focus on leading and following techniques that stem from the basic moves that are used to create a series of interconnected moves that we then end up calling a “turn pattern.” It would also be more beneficial to focus on giving learners the tools to put together different moves and create their own turn patterns—because isn’t that what instructors do when they come up with what they’ll teach? Even at the basic level, this can be done. Many a time I’ve taught in my casino lessons only three very basic moves and then shown some of the ways they could be combined to last an entire song so that it does not feel repetitive—and then encouraged students to find their own combinations of these same moves during practice. In other words, learners should be given the space to lead and follow whatever they feel they have the skill to lead and follow from what was taught in the lesson—and then, with the help of the instructor, be pushed to do just a little more. (This is another concept from the language classroom, known as “i+1”.)

Furthermore, learners knowing what is expected of them—and what they can expect from instructors—is paramount. Don’t ever think that expectations are implied. Short- and long-term expectations need to be made explicit in every lesson. The first step toward pushing learners to become more autonomous dancers is them knowing that the expectation that is set for any dance lesson is not buttressed on the idea that they must first know a number of turn patterns before they can really dance (that’s the implicit message in most turn pattern-centered lessons), but rather on the idea that learners at any level can dance by using what they know to create a dance experience that adjusts to their skills (I’ve always said that I’d rather do five moves all the time, and do them well, than do a hundred mediocre ones). If this is what is expected, learners will be more inclined to accept the new class dynamics in which students are the stars, and not the instructors—especially those who think the instructor is the sole factor in dictating whether or not learning occurs (not true)—, be more encouraged to learn to dance, and ultimately feel more rewarded when they do attempt to dance outside of the class setting.

By way of conclusion, I would like to point out that, with this post, I am not attempting to provide a definitive way of conducting a lesson. This is what I have found works for myself, based on my own experiences. At the same time, I understand that not all classes are the same; not all learners have similar needs; not all instructors share a uniform background. Other academies may use different strategies that work as well in getting their students to being autonomous dancers. And maybe you try this and find that it doesn’t work. Perhaps you find out that 20% of class time devoted to instruction is too little.

Whichever the case, what I seek to do here is to open the floor for a much-needed conversation about methodology.