In the context of the United States, the ascribed “Latinness” of the dance of salsa has always perplexed me. Many call salsa a “Latin dance”—a dance from Latin America—but when it comes to the way that we dance salsa in this country, the places of origins of the two styles of salsa which we know and dance tell a different story. Indeed, we don’t need to be geography experts to notice that the New York (on-2) or the Los Angeles (on-1) styles of salsa refer to places which do not belong to Latin America.

Hence the title of this piece.

Given that salsa dancing stemming from the U.S. cities of New York and Los Angeles is often unquestioningly considered “Latin” by many, in order to understand this “Latinness” and come out of my perplexed state, I had to ask myself the following question:

What is considered “Latin” in the United States when it comes to dancing?

It had to be something different from what I understood the term “Latin” to be; that is: originating in Latin America. Once I could established what was understood by “Latin” in this country, I could then assess the Latinness of salsa dancing, in its New York and Los Angeles styles. I could then answer: How Latin is the dance of salsa?

So that’s where Part 1 of this article came in: it attempted to answer what was considered “Latin” in this country, to begin with. (Read Part 1 here.) And to answer it, I had to go all the way back to the early 1900s; for that is when the concept of Latin dancing came to the United States, using the ballroom to do so. I found that what arrived to the U.S. were “concepts”—as opposed to dances. Indeed, through ballroom, dances from Latin America such as tango and son (called “rumba” in ballroom) underwent a radical recodification to conform to the aesthetics of middle and upper class white people, as they were the ones who paid ballroom studios for their lessons. In the words of Juliet McMains, who extensively studied the ballroom industry in her book, Glamour Addiction: Inside the American Ballroom Dance Industry, through ballroom, Latin dances became “Western appropriations with only limited similarity to forms practiced in Latin America and that rely extensively on Western stereotypes of Latinness for their emotional and aesthetic appeal” (112).

As it turned out, when it came to Latin dances in the U.S., the “Latinness” of these dances was only found in the name. Most of everything else had very little to do with Latin America.

Would it be viable, then, to suggest that what we consider to be a Latin dance—salsa—given what “Latin” has meant for more than a century in this country’s dance industry, is actually not from Latin America, but more of a U.S. dance “with only limited similarity to forms practiced in Latin America and that rely extensively on Western stereotypes of Latinness for their emotional and aesthetic appeal”?

I think so. And that’s what Part 2 is about.

So, let’s pick up where Part 1 left off: the aftermath of the Palladium mambo era.

The Latin hustle years: the 70s

Iin her article “What’s in a Number? From Local Nostalgia to Global Marketability in New York’s On-2 Salsa”, Sydney Hutchinson points out that after the Palladium closed in 1966, “the dance developed in new directions, from boogaloo to hustle and finally to salsa. During this period, the place of salsa music shifted dramatically, going from the ballroom to the street” (32). And with the music going out into the street, so did the dancing.

But it wasn’t the mambo of the Palladium ballroom that was being danced. As Hutchinson notes: “many talented young dancers in the 1970s were drawn to the more demanding Latin hustle, a dance that grew out of swing and featured a slot format, fast spins, lifts, and distinctive turn patterns.” In fact, it became so popular, that “the hustle quickly eclipsed Palladium mambo in popularity” (Hutchinson 33). Angel Rodriguez—a dancer who will become important in the 80s for reasons we will see soon—told Hutchinson in an interview: “The hustle came out of a bunch of Puerto Ricans that didn’t want to do salsa…. The basic step came from the black hustle, which was a three-step dance, and all that influence combined with all the ballroom movies coming out at the time (33; my emphasis).”

As with the other “Latin” dances before it, including the Palladium mambo, the Latin hustle was not really “Latin.” One could argue—though without much success—that it could be Latin because it was developed by Puerto Ricans. But the 70s was the decade in which the term “Latino” came about. Indeed, according to Arlene M. Dávila, the term “Latino” and “Hispanic” were first generally used in the 1970s by federal agencies in the United States to describe people of Latin-American decent living in this country (2); so technically Puerto Ricans living in the States at the time would have been considered Latinos, not Latins. At any rate, calling Latin hustle a “Latino dance” undermines the contributions of African American hustle, as well as the U.S. dance from which Latin hustle grew out, according to Hutchinson: swing. (As a side note here, I want to mention that swing “became acceptable in the ballroom only after references to the black culture out of which they emerged had been sufficiently erased” [McMains 112]).

Talking about swing: do notice that Hutchinson above asserts that Latin hustle “featured a slot format, fast spins, lifts, and distinctive turn patterns.” To anybody who dances salsa or has watched a salsa performance, that should sound very familiar. Also, one thing that I would like to point out from what Rodríguez said is that ballroom, even as the dancing took to the street, still played a role in the development what was considered a “Latin dance.”

And it would do so, again, with the “revival” of mambo in New York in the 80s.

The emergence of modern-day salsa dancing: the late 80s and early 90s

What we known today as “mambo” (salsa on 2) is not the Ballroom mambo of the 50s and 60s. Eddie Torres, the person credited with the creation of the best-known on-2 teaching method in the late 1980s, and who is also known as “The Mambo King,” explains in his biography that:

When Latin dance first came to NY, it was an open position dance. That means that two dancers would dance in front of each other and there was not much contact, what we know today as partner work. But the second generation after the Palladium got into doing a lot of partner work.

What Eddie Torres did was a generational reinterpretation of the Palladium mambo, much like what happens to movies made decades ago which now get a remake. Torres’ mambo was different than the Palladium mambo, and judging by the description of mambo he himself provides, it was greatly influenced by what Latinos in New York had been dancing at the time: Latin hustle—which in turn, as we have seen, comes from swing and has influences of ballroom as well as basic steps from African American hustle.

Torres’ mambo had dancers focus on counts, which uses 123-567, with a break, or direction change, occurring on counts 2 and 6. This was different from the mambo of the 50s, since the Palladium mambo used the ballroom counts of the ballroom “rumba” (234). In this interview, Torres says that he calls the 123 the “street version,” while the 234 is the “studio version.” This can be seen as an attempt to legitimize—and make more authentic—his version among dancers who did not want to be associated with ballroom.

Yet Eddie Torres, from the very beginning, set out to “see Latin dancing evolve to the point of a respected, classic art form” (his biography). Torres did not want to “revive” mambo, per se, as much as he wanted to evolve it. On the other hand, that respect that he wanted for Latin dancing had a very specific public: white Americans. In this country, they were the ones who could ultimately decide whether or not what he was doing could be considered not only art, but classic art—a term that has a Euro-centric perspective written all over it.

So it should not come as a surprise that Eddie Torres had the help of a ballroom dancer to create his syllabus and codify the dance that he would call “mambo.” In effect, Torres “teamed up with ballroom instructor June LaBerta, who encouraged him to put counts to his dancing, to name his steps, and to create a syllabus” (Hutchinson 33). With LaBerta’s help, Torres did what ballroom has done to any dance since the 1870s: codify; standardize.

Now, with this I am not saying that Eddie Torres’ mambo is a ballroom dance. It isn’t—entirely. As Hutchinson notes, today, salsa “occupies a more ambiguous place, somewhere between the two poles of street and studio” (32). And that is just the thing: because of how Torres’ mambo was developed, no matter how “street” you think salsa is and how different you see yourself from a ballroom dancer, the dance has undeniable influences from ballroom. Indeed, on-2 salsa (or mambo) is “clearly a studio-based practice, and as such it is clearly distinct from salsa as practiced in a home setting” (Hutchinson 37).

Even the alternative school of on-2 dancing which was developed by Angel Rodríguez, simultaneously with that of Eddie Torres’, was devised at a ballroom: Paul Pellicoro’s Manhattan ballroom studio. This alternate way of dancing on-2 would become the Razz M’Tazz (RMT) system (Hutchinson 34).

Ballroom was also present in the development of salsa on-1 in Los Angeles in the early 90s. As Jonathan S. Marion states in his article “Contextualizing Content and Conduct in the L.A. Salsa Scene,” “early versions of Los Angeles-style salsa were more heavily influenced by West Coast Swing and Latin ballroom dancing” (66).

Here is a video of West Coast swing, a U.S. dance. You tell me what this looks like:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KMiFYJFRoIQ&w=560&h=315]

In short, when it comes to salsa dancing, in either its on-1 or on-2 styles, the influences from ballroom can neither be discarded, nor denied. Nor can we deny or discard how much U.S. dances shaped what we know today as salsa. Indeed, as Rodriguez explains in this video: “hustle and swing gave birth to all the mambo turns.” Toward the end of the video, he says the following: “If you do one dance [either hustle, swing, or mambo], you should be able to do them all.” These three dances, to him, are “kissing cousins.”

Now, Part 1 of this article established how ballroom created the idea of Latin dancing in the U.S.: by developing dances that conformed to U.S. aesthetics of the time while being steeped in stereotypes of Latinness. In other words, ballroom developed U.S.-based dances and branded them as “Latin” to create a desire for consumption of what was deemed as an exotic/foreign product when it was really not.

Given that the salsa dance that we know today is a product of the process of codification and standardization intrinsic to ballroom and whose result has very little to do with Latin America, what is it that makes us believe that salsa dancing, as we know it on its on-1 and on-2 styles, is a “Latin dance”—that is, a dance from Latin America—even as we acknowledge that it was developed in the U.S.?

See? Perplexing stuff.

The global commercialization of sabor: the 90s

During the 1990s, “on-2 dancing became a codified, commercial product sold though lessons and congresses” (Hutchinson 35). It was also the decade in which U.S. salsa dancers were able to take what they had learned at the academies and experience it in a more “authentic setting,” outside of the U.S. mainland. 1997 marked a pivotal moment in the perception of salsa dancing as “Latin” because it was the year of the World Salsa Congress (now called the Puerto Rico Salsa Congress). The fact that people experienced en masse a dance they believed was a product of Latin America in Puerto Rico—which by the way is a Commonwealth of the U.S. and whose inhabitants have been U.S. citizens since 1917—cemented this idea. As Priscilla Renta states in her article, “The Global Commercialization of Salsa Dancing and Sabor (Puerto Rico),” the congress “transformed salsa dancing into an official symbol or display of Puerto Rico nationhood” (133). To many outsiders who had learned to dance on-1 or on-2 salsa in the States, a salsa congress in Puerto Rico served as proof that salsa was unquestionably Latin.

Then there is Puerto Rican-style salsa itself, which according to Renta, “is associated with sabor, improvisation, and polycentricism” (135). Let’s break this down a bit, as it is important to understand what this means in the context of ballroom-developed Latin dances.

Polycentrism is a concept that has arisen though analysis of Africanist dance aesthetics. Brenda Gotsschild explains the concept more clearly: “movement may emanate from any part of the body, and two or more centers may operate simultaneously. Polycentrism diverges from the European academic aesthetic, where the ideal is to initiate movement from one locus: the noble, upper center of the aligned torso, well above the pelvis” (333).

On the other hand, improvisation in ballroom, according to Sheenagh Pietrobruno, had been “largely eliminated from [Latin] dances through the standardization process imposed by the dance industry” (118).

As far as sabor goes, well, let’s just say that when it comes to ballroom-derived dances, the noun you’re most likely to hear is “elegance,” not “flavor.” So the concept of “flavor” also falls outside of ballroom. Moreover, according to Renta, “dancing salsa with sabor serves as a symbolic form of cultural nationalism” (118).

So here you had a way of dancing salsa which was unlike any “Latin” dance that had come out of the ballroom, or had been developed in the U.S. using ballroom concepts.

But it wasn’t the type of salsa dancing that was or is promoted at the Puerto Rico congress. As Renta explains, the salsa congress “focuses on staged, choreographed salsa dance performance and competitive dancing” (118). Choreographing something is the exact opposite of improvising it. Furthemore, “the predominance of turn patterns relates to the ballroom dance industry’s influence, which has made way for competitive salsa dancing” (134).

Interestingly enough, rather than attempt to do away with “flavor,” ballroom has decided to bank on it. The World Salsa Federation, for example, which was founded by ballroom dancers Isaac and Laura Castro Altman, has been at the forefront of the global commercialization of sabor (Renta 127). It promotes its DVD, Latin Body Rhythms, thus: “A must if you want to dance Salsa with the maximum body action and SABOR!”

Ballroom, once again, had come out to play.

And Puerto Ricans living in the island didn’t fail to notice. As Renta explains, “the competitive salsa dancing the congress brought to Puerto Rico was influenced by what many [in Puerto Rico] describe as salsa de salón, ballroom salsa, which emphasized Europeanist aesthetic values over Afro-Caribbean sensibilities” (135). This salsa de salon was perceived as “a more linear form that focuses on lengthening the body” (Renta 136).

Ironically, what people in the States perceived as “street” salsa, separated from the practices of ballroom, in Puerto Rico was perceived as a ballroom dance.

What happened at the Puerto Rican salsa congress was a reformulation of stereotypes about Latin American dances; a re-branding, if you will. If U.S.-developed “Latin” dances of the first half of the 20th century, like tango and rumba, were associated with “passion,” which played into the fantasies of middle class men and women of the time, U.S. developed salsa dancing does something very similar. Through the emphasis on sabor, a concept alien to ballroom both in sound and in execution, a ballroom-based/influenced dance like salsa/mambo was able to retain its “Latinness” even if its very origin (New York/ Los Angeles) dictated otherwise.

Concluding thoughts (finally)

The “Latin,” as it pertains to dancing in this country, is a concept which relies on old and new stereotypes the U.S. has of Latin America. Sexy, hot, sizzling, sensual, caliente. These are adjectives which are often used in the Latin dance scene. All of them help create what I call a “Latin atmosphere,” where the nationality of the dance does not really matter; for an atmosphere, as cultural critic Gustavo Perez-Firmat asserts, “has no history, no borders, no flag…[and] breeds denationalization” (17-18). That’s why a dance like kizomba, a dance from Angola, can make its way into Latin dance scene uncontested. And though one could make the argument that kizomba can do this because Angola was a colony of Portugal until recently, I can similarly ask, why don’t dances and music from Brazil—another former Portuguese colony and which actually happens to be in Latin America—make it into a Latin dance social or congress? My answer: because they don’t fit the stereotypes on which our “Latin dance” atmosphere has been built, thanks to the Euro-centric (Western), ballroom-influenced aesthetics in place in this country for more than a century.

Positioning Latin dancing within the context of the ballroom is not only necessary if we are to create a historically-conscious narrative of salsa dancing, it is key to understanding what we perceive as a “Latin dance” in this country. As we have seen, ballroom practices and aesthetics have always been there to help define what constitutes a Latin dance, from the first tango danced in the U.S., to the Palladium mambo, to Eddie Torres’ New York-style salsa, to L.A.-style salsa, to the push toward competitive salsa at the Puerto Rico Salsa Congress, even to the way people dress up for performances. Ballroom has had an undeniable presence in the development of what we know today as salsa.

And to this day, what constitutes a “Latin dance” inside the ballroom— that is, a Western-appropriated dance with only limited similarity to forms practiced in Latin America and that rely extensively on Western stereotypes of Latinness for their emotional and aesthetic appeal—is still what constitutes a “Latin dance” outside of it.

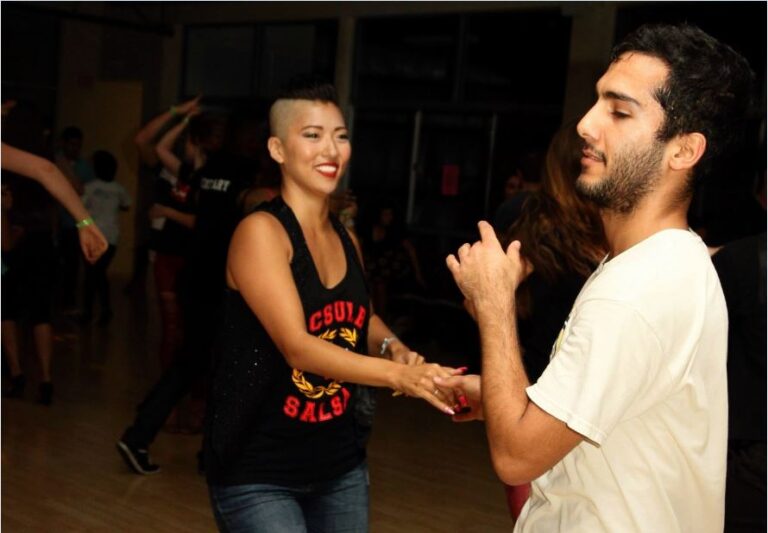

The salsa that you know and dance, in its on-2 or on-1 styles, did not come from anywhere in Latin America. It was developed right here, in the States, out of U.S. dances like hustle and swing—dances which were already entrenched in ballroom (Western) aesthetics. And we’re still relying on ethnically-charged stereotypes of “Latinness” such as sexiness, sensuality, and temperature-related adjectives such as “hot” to sell the dance. In fact, isn’t the silhouette of the picture to the right the one that you see most often used when you see a poster for a salsa dance class? And if you were to type “salsa dance” on Google Image, that is one of the first pictures that would show up. (The picture that I chose for the header of the article was not picked at random, either.)

With all this information in mind, you now have two options.

Option A: You could either keep calling salsa a “Latin dance,” knowing fully well that this is not the case, as I have extensively demonstrated above.

Option B: You could stop calling it a “Latin dance” and try to figure out a better label for it. I’ve been trying to do that myself, and have not been able to arrive at an answer just yet. It’s quite the conundrum. You see, on the one hand, calling salsa a “Latino dance” acknowledges the role that Latinos (see Dávila’s definition above) played in the development of modern-day salsa, but undermines the role that ballroom and U.S. dances like swing and hustle had as well. And if we call it a “U.S. (American) dance,” while it acknowledges the importance of swing and hustle and ballroom, it erases the contributions of Latinos like Eddie Torres.

Like I said, I don’t have an answer. But what I do know is that whatever label we do come up with—if we choose Option B—has to acknowledge both Latinos/as and U.S. contributions to modern-day salsa dancing that we practice in the United States.

Works Cited:

Dávila, Arlene M. Latinos, Inc.: The Marketing and Making of a People. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001. Print.

Gottschild, Brenda. “Stripping the emperor: The Africanist presence in American concert dance.” Moving History/ Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Ann Dills and Ann Cooper-Albright, eds. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001. Print.

Hutchinson, Sydney, ed. “What’s in a Number? From Local Nostalgia to Global Marketability in New York’s On-2 Sals.” Salsa World: A Global Dance in Local Contexts. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014. Print.

Marion, Jonathan S. “Contextualizing Content and Conduct in the L.A. Salsa Scene.” Salsa World: A Global Dance in Local Contexts. Sydney Hutchinson, ed. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014. Print.

McMains, Juliet E. Glamour Addiction: Inside the American Ballroom Dance Industry. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2006. Print.

Pérez Firmat, Gustavo. The Havana Habit. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. Print

Pietrobruno, Sheenagh. Salsa and Its Transnational Moves. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2006. Print.

Renta, Priscilla. “The Global Commercialization of Salsa Dancing and Sabor (Puerto Rico).” Salsa World: A Global Dance in Local Contexts. Sydney Hutchinson, ed. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014. Print.